-

-

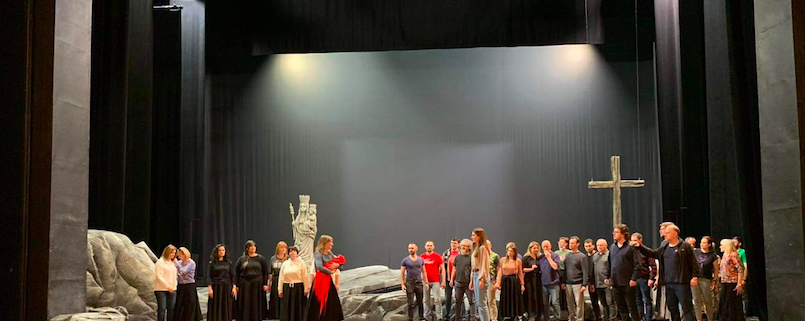

“Kniaź Igor”

-

-

“Straszny Dwór”

-

-

“Turandot”

-

-

“Wolny Strzelec”

Dziś po spektaklu Toski odbędzie się benefis solisty naszej opery Radosława Żukowskiego, który występował na scenach oper i filharmonii w kraju i na świecie, z sukcesem brał udział w wielu międzynarodowych festiwalach, jest laureatem licznych konkursów, odznaczony Brązowym Medalem “Zasłużony Kulturze Gloria Artis”.

Nie wystarczy pięknie zaśpiewać, trzeba mieć coś do powiedzenia mówi Radosław Żukowski w rozmowie z Katarzyną Aszkiełowicz.

Kończy Pan pracę artystyczną w Operze Wrocławskiej – Wrocław to ważne miejsce w pańskiej karierze?

Odchodzę z Opery Wrocławskiej po wieloletniej pracy – pierwszą umowę podpisałem w 1977 roku. Zaczynałem w chórze jako student, a od 1982 roku śpiewałem już jako solista. Tu się wszystko zaczęło, zresztą jestem wrocławianinem od urodzenia. Gdziekolwiek bym nie pracował na świecie, zawsze byłem związany z Wrocławiem. Jestem profesorem Akademii Muzycznej im. Krzysztofa Pendereckiego w Krakowie – mieszkam we Wrocławiu. Pracowałem w Niemczech w latach 80. w teatrze – a jednocześnie też pracowałem i żyłem we Wrocławiu.

Ciągle jednak był Pan w podróży…

Artyści z racji swojego zawodu są bardzo ruchliwi. Czasami nie wiedziałem, gdzie mam swoje rzeczy, bo migrowałem między trzema – czterema miejscami. Tak się pracowało i żyło. Lubiłem muzykę, lubiłem sztukę, więc nie przeszkadzało mi to. Wtedy nawet niedogodności sprawiały przyjemność, a poza tym ta mobilność pozwalała mi poznawać innych wykonawców, twórców, co było bardzo rozwijające, szczególnie dla młodego artysty.

Poznał Pan opery w wielu krajach i ich życie od środka -która Panu jest najbliższa?

Sztuka zawsze łączy ludzi – zbliża niezależnie od kraju, widzę to wykonując muzykę oratoryjną na całym świecie. Szczególne miejsce w moim sercu zajmuje Portugalia. Dla Portugalczyków Europa to ,,mały kraj”, bo oni myślą całym światem. Mają niesamowite muzea, zachowaną historię wieków – widać ją nawet na szklankach pozostawionych w pałacach, które mają ślady odcisków palców ich dawnych właścicieli. Tam są zupełnie inne konteksty pojmowania człowieka. Znajomy Ślązak, którego poznałem w Portugalii, powiedział mi, że gdy mieszkał w Polsce, nazywano go Szwabem, gdy wyemigrował do Niemiec, słyszał, że jest ,,brudnym Polakiem”. Przyjechał do Portugalii, i zapytali go: kim ty jesteś jako człowiek? Wiele nauczyłem się od Portugalczyków. Wspólnie jedliśmy, żyliśmy, rozmawialiśmy i tak jak Picasso, zapisywaliśmy nasze pomysły na serwetkach. Spędziłem tam osiem lat i to był fantastyczny czas. Zacząłem od roli Komandora w Don Giovannim. Prawdziwą Portugalię tamtejsi muzycy pokazali mi dopiero po 2-3 latach, kiedy się już dobrze poznaliśmy.

Kusiło Pana żeby zostać Portugalczykiem?

Zawsze przede wszystkim chciałem być sobą. A jesteśmy tym, co wynosimy z domu, kształtują nas doświadczenia i lata pracy, a także to, co dali nam inni ludzie. Im większy bagaż doświadczeń, tym więcej mamy do powiedzenia. Dlatego do pewnych ról się dorasta. Owszem, w młodym wieku można technicznie coś pięknie zaśpiewać – ale co mamy publiczności do powiedzenia?

Kiedy Pan polubił muzykę?

Od małego ją lubiłem. W moim domu zawsze były instrumenty, więc nieustannie mi towarzyszyła, miałem ją dosłownie we krwi. Oboje z mamą skończyliśmy tę samą uczelnię,

z tym że moja mama miała dyplom numer 13, a mój miał 1213. Tysiąc dwieście dyplomów później dołączyłem do mamy i grona absolwentów Akademii Muzycznej we Wrocławiu. Ojciec był leśnikiem, ale fantastycznie grał na fortepianie.

Otrzymał Pan zatem solidną wyprawkę na swoją muzyczną drogę, a kiedy rozpoczęła się na poważnie – w czym Pan debiutował?

Rolą Księcia Gremina w Onieginie Czajkowskiego. Wcześniej w ramach dyplomu śpiewałem Falstafa w Wesołych kumoszkach, a w czasie studiów występowałem w Fidelio jako chórzysta i to był mój pierwszy kontakt zawodowy z operą w 1977. Zaczynałem wtedy z Jurkiem Szlachcicem, który też śpiewa w naszej operze.

Zanim jednak po raz pierwszy pojawiłem się na scenie, droga oczywiście była długa. Moja mama była bardzo przeciwna, bym został muzykiem. Obawiała się, że nie poradzę sobie finansowo, bo to bardzo niepewny, ciężki zawód itd. itp.. Odpowiadałem jej wtedy, że tu przynajmniej jest sprawiedliwość – jeśli będę dobry, wszystko będzie w porządku. Po dziś dzień podziwiam swoją naiwność! 🙂 Kiedy podjąłem decyzję, mama mnie oczywiście w niej wspierała – widziała jak bardzo mnie ciągnie do muzyki. Przyniosła mi formularz – pracowała w szkole muzycznej i chórze Polskiego Radia – i zdałem na wydział wokalno-aktorski Wyższej Szkoły Muzycznej. Ogrom pracy, talent, łut szczęścia pomogły mi iść dalej. Owocem tego był m.in. wspomniany kontrakt z operą w Lizbonie oraz z innymi operami i filharmoniami w Europie i na świecie. Prócz oper śpiewałem oratoria – prawdziwe sanatorium dla śpiewaka dla operowego!

Teraz śpiewa Pan Barona Scarpię w Tosce – co Pan mówi tą rolą?

Gram specyficzną postać. Baron Scarpia stara się zdobyć kobietę, zmaga się z problemem świata damsko-męskich intryg. Ograniczają go wiek, stanowisko szefa policji. Wygrywa piękny, młody tenor, a Scarpia… Jeżeli artyście uda się zespoić z postacią, to już jest sukces. Publiczność nie znosi fałszu. Daję swojemu bohaterowi to, co mam, a na pewno mogę dać prawdę moich uczuć, emocji. Ale prywatne życie trzeba zostawić za kulisami, nie mieszać tych dwóch światów.

Potrafi Pan je rozdzielić?

Kiedyś jeden z moich kolegów, jeszcze z czasów studiów, podszedł do mnie na pikniku urządzanym przez moją sąsiadkę i dobrą koleżankę ze szkoły muzycznej:Jestem w szoku, ty jesteś zupełnie inny! Odpowiedziałem mu: Bo jestem w domu, za tym płotem zostawiam to, kim jestem zawodowo. Rozdzielenie tego kim i jacy jesteśmy w domu, od tego, co na scenie i w pracy to kwestia dyscypliny, idą za tym lata pracy.

Miał pan swojego mentora, który tego pana uczył czy raczej to kwestia doświadczenia?

Prof. Irena Gałuszka. Fantastyczny człowiek i pedagog. Dużo ode mnie wymagała, dyscyplinowała mnie, ale też poświęcała mi wiele czasu. Zawsze byłem do jej dyspozycji, to chyba była moja największa zaleta! Sporo się od niej nauczyłem.

Pan też jest teraz takim nauczycielem?

Staram się, ale nie wszystko ode mnie zależy. Są studenci i studentki, którzy z tego korzystają i można z nimi efektywnie pracować, a inni liczą tylko na szczęście i czekają na szybkie sukcesy. A wszyscy artyści wiedzą, że dzieło potrzebuje czasu – musi się uleżeć! Chociaż muszę przyznać, że sama wiedza w sztuce scenicznej nie wystarczy, ale żeby coś osiągnąć trzeba mieć solidne podstawy techniczne. Używając metafory językoznawczej, sceną rządzi nie tylko gramatyka, stałe zasady, które decydują o poprawności naszej składni. Musi być jeszcze odbiorca naszego komunikatu i to, co dajemy od siebie. Wtedy sztuka może zaistnieć. Kiedyś stanąłem na scenie i powtarzałem sobie w głowie to, co zawsze mówię studentom, pilnuj tego…pilnuj tamtego… aż pomyślałem, człowieku, co ty robisz, tak się nie da! Technika jest niezwykle ważna, ale jeszcze ważniejsze jest tylko środkiem do tego, co chcemy przekazać publiczności.

Pańskie szczególne role w karierze, które właśnie wymagały tej triady?

Faust, Nabucco, Czarna Maska, Tosca… Na Toskę namówiła mnie moja żona Aleksandra Lemiszka, wieloletnia solistka Opery Wrocławskiej.

Zdarzało Wam się śpiewać wspólnie?

Pewnie, że tak!

Podejrzewam, że może być to trudniejsze niż w przypadku duetu z neutralną osobą…

To jest najtrudniejsze! To tylko pozór, że w duecie z żoną można pozwolić sobie na więcej, wręcz przeciwnie! Weźmy taką scenę gwałtu. Grana z bliską osobą wymaga wyjątkowego oddzielenia świata prywatnego od zawodowego, a jeszcze trzeba uważać, żeby przypadkiem na tren sukni nie nadepnąć, bo w domu można bęcki dostać (śmiech). Ale cóż, teatr to miejsce oparte na relacjach, wspólnocie, musimy umieć ze sobą żyć, bo to zgrany zespół tworzy instytucję – ją można zlikwidować jednym podpisem, ale zbudowanie na nowo zajmuje lata. Wszyscy pracujemy w jedności: artyści śpiewacy, muzycy orkiestry, technika, pracownia krawiecka. Trzeba mieć tego świadomość, że jesteśmy miejscem zbudowanym na wzajemnych relacjach.

By utrzymać dobre relacje w tak wielkiej wspólnocie na pewno trzeba cierpliwości i przede wszystkim pokory…

Święte słowa, sztuka wymaga wielkiej pokory.

Pan jest pokorny?

Myślę, że to inni powinni ocenić.

To bardzo pokorna odpowiedź! Po tylu latach spędzonych w operze, czego Pan się tutaj nauczył?

Mogę wyjść i zaśpiewać Barona Scarpię w taki sposób w jaki śpiewam i powiedzieć sobie starczy. Nauczyłem się też publiczności, tego, jak potrafi ona reagować, jaką energię i uwagę potrafi przekazać artyście. Pamiętam moment, gdy stałem na scenie i czułem, że ta cisza, to przeciwne napięcie, które ludzie na widowni kierują w moją stronę – że to wszystko w tamtym momencie było moje.

Nauczyłem się też, że praca solisty to nie tylko śpiew. To aktorstwo, ruch i inne dodatkowe umiejętności, które składają się na ostateczny efekt. Na wydziale wokalno-aktorskim przez trzy lata graliśmy sztuki dramatyczne, i trzy lata – operę. Uczyliśmy się takich niuansów jak to, w jaki sposób trzyma się papier czerpany, a jak pisze się gęsim piórem. Wszystko wymaga innej gry na scenie! Trzeba wiedzieć, jak upaść na podłogę, jak tańczyć. Po co był mi balet? Uczyłem się go kilka lat, wiedząc, że tancerzem nie zostanę, ale za to miałem większą pewność, że gdy obrócę się kilka razy na scenie, to się nie wywrócę.

To mocne fundamenty pod to, co ostatecznie stało się Pana przeznaczeniem, czyli śpiew…

Co też wymagało czasu i wspomnianej pokory – wiedziałem, kiedy ma przyjść moja kolej, a kiedy jeszcze muszę zaczekać. Pierwszą propozycję, rolę Zachariasza w Nabucco, dostałem tuż po studiach w operze w Bytomiu, do tego ofertę trzypokojowego mieszkania. Odmówiłem. Wiedziałem, że było dla mnie za wcześnie. Dopiero 10 lat później zaśpiewałem w Nabucco w Teatrze Wielkim w Warszawie. Potem te partie śpiewałem wielokrotnie w różnych teatrach.

Moja profesorka śpiewu mówiła mi, bym pamiętał o spokoju, technice, a potem dopiero o interpretacji. Co więcej, twierdziła, że nie jestem gotów na konkursy! A ja i tak w nich brałem udział, bo chciałem się sprawdzić, poddać się ocenie innych ludzi, zobaczyć, ile jeszcze mi brakuje, by stać się artystą.

Wzrusza się Pan podczas spektakli? Emocje to jeden ze składników dobrego występu, ale z drugiej strony, mogą go też zepsuć…

Nie pozwalam sobie na to. Pamiętam jak śpiewałem w czasie pierwszej komunii własnego syna, ten ścisk w gardle – nigdy więcej! Znam przypadek, kiedy jedna ze śpiewaczek tuż przed występem otrzymała wiadomość, że jej córka miała wypadek i jest w ciężkim stanie. Artystka zaniemówiła na pół roku, emocje wymknęły się spod kontroli.

Istnieje życie pozaoperowe? Niedługo będzie miał Pan nieco więcej czasu na odpoczynek, zwolnienie tempa…

Planuję przede wszystkim normalność, nie planuję zbyt wiele zgodnie ze staropolskim powiedzeniem Człowiek planuje, Pan Bóg zapisuje. Jestem człowiekiem spełnionym. Mam rodzinę, dom, wnuki i czas na uwolnienie się od tego wiecznego pędu, ciągłych komplikacji w życiu. A każdy ma jakieś problemy – na starość chce się stabilizacji, spokoju i przede wszystkim zdrowia. Patrzę czasem na swój telefon, widzę, ile numerów już nigdy nie odbierze ode mnie połączenia, ale ja nigdzie na razie się nie wybieram! Chyba, że na wygodny fotel, by spędzić czas z wnukami. W dzieciach jest prawda, radość i otwartość na drugiego człowieka. Uwagę i wiedzę o świecie trzeba przekazywać im od najmłodszych lat, nawet, gdy ich oczy są jeszcze trochę mętne, gdy dopiero uczą się patrzeć na świat. Tylko tak wychowamy następne pokolenia. Przekazując im prawdę oraz ucząc tolerancji i szacunku wobec drugiego człowieka. A nauczymy ich tego tylko wtedy, kiedy one będą widziały te wartości w nas.

Rozmawiała Katarzyna Aszkiełowicz

45 years on stage of Radosław Żukowski!

Today, after the opera Tosca, there will be a performance in honour for the soloist of our opera, Radosław Żukowski, who has performed on the stages of operas and philharmonics in Poland and abroad, successfully participated in many international festivals, and a laureate of numerous competitions, awarded with the Bronze Medal “Gloria Artis for Services to Culture”.

It is not enough to sing beautifully, you need to have something to say too, says Radosław Żukowski in an interview with Katarzyna Aszkiełowicz.

You are ending your artistic work at the Wrocław Opera House – is Wrocław an important place in your career?

I am leaving Wrocław Opera after many years of work – I signed my first contract in 1977. As I started in the chorus as a student, and from 1982 was I already singing as a soloist. This is where it all began, by the way I am a citizen of Wrocław since I was born. Wherever I have worked in the world, I have always been connected to Wrocław. I am a professor at the Krzysztof Penderecki Academy of Music in Kraków – and I live in Wrocław. I worked in Germany in the 1980s in the theatre – and at the same time I also worked and lived in Wrocław.

But you were constantly on the move…

Artists are very mobile because of their profession. Sometimes I did not know where all of my things were, because I migrated between three or four places. That was how I worked and lived. I liked music, I liked art, so it didn’t bother me. At the time, even the inconveniences were fun, and besides, this mobility allowed me to meet other performers, artists, which was very developing, especially for a young artist.

You have seen opera houses in many countries and their life from the inside – which one is closest to you?

Art always brings people together – it brings people together regardless of the country, I see this by performing oratorio music all over the world. Portugal holds a special place in my heart. For the Portuguese, Europe is ‘a small country’, because they think in terms of the whole world. They have incredible museums, preserved history of centuries – you can see it even in glasses left in palaces, which have traces of fingerprints of their former owners. They have a completely different understanding of the human being. A Silesian friend, whom I met in Portugal, told me that when he lived in Poland, he was called a Kraut, and when he emigrated to Germany, he was told he was a “dirty Pole”. He came to Portugal, and they asked him: who are you as a person? I learned a lot from the Portuguese. We ate together, we lived together, we talked together and, like Picasso, we wrote down our ideas on napkins. I spent eight years there and it was a fantastic time. I started with the role of the Commodore in Don Giovanni. They only showed me the real Portugal after 2-3 years, when we got to know each other well.

Were you tempted to become Portuguese?

Above all, I always wanted to be myself. And we are what we bring from home, shaped by our experiences and years of work, as well as what other people have given to us. The more experience we have, the more we have to say. That is why you grow into certain roles. Yes, you can technically sing something beautiful at a young age – but what do we have to say to the audience?

When did you become fond of music?

I liked it from a very young age. There were always instruments in my house, so it was always with me, it was literally in my blood. My mother and I both graduated from the same university. Except that my mother’s diploma was number 13 and mine was 1213. My father was a forester, but he played the piano fantastically.

So you received a solid training for your musical journey, and when did you start seriously – in what did you make your debut?

The role of Prince Gremino in Tchaikovsky’s Onegin. Before that I sang Falstaff in The Merry Wives as part of my degree, and during my studies I performed in Fidelio as a chorister and that was my first professional contact with opera in 1977. I started then with Jurek Szlachcic, who also sings in our opera.

But before I got on stage for the first time, the road was of course long. My mother was very much against me becoming a musician. She was afraid that I wouldn’t be able to cope financially, because it’s a very uncertain, difficult profession. I told her at the time that at least there was justice – if I was good, everything would be fine. To this day I marvel at my naivety! When I made my decision, my mother supported me in it of course – she saw how much I was drawn to music. She brought me a form – she worked in a music school and in the choir of the Polish Radio – and I passed my entrance exams to the vocal-acting department of the Music Academy.

A lot of work, talent and luck helped me to go further. This resulted, among other things, in the aforementioned contract with the Lisbon Opera and with other opera houses and philharmonics in Europe and around the world. Apart from operas, I sang oratorios – a real sanatorium for an opera singer!

You are now singing Baron Scarpia in Tosca – what do you say with this role?

I play a specific character. Baron Scarpia tries to win a woman, struggles with the world of male-female intrigue. He is limited by his age and his position as chief of police. A beautiful young tenor wins, and Scarpia… If the artist manages to unite with the character, it’s already a success. The audience hates falsehood. I give my character what I have, and I can certainly give the truth of my feelings, my emotions. But you have to leave your private life behind the scenes, don’t mix these two worlds.

Can you separate them?

Once one of my colleagues, still from my university days, approached me at a picnic organised by my neighbour and good friend from music school: I am shocked, you are completely different! I answered him: Because I am at home, behind this fence I leave who I am professionally. Separating who and what we are at home from what we are on stage and at work is a matter of discipline, it takes years of work.

Did you have a mentor who taught you this or is it a matter of experience?

Prof. Irena Gałuszka. A fantastic person and teacher. She demanded a lot from me, she disciplined me, but she also sacrifice me a lot of time. I was always at her disposal, which was probably my greatest advantage! I learned a lot from her.

Are you also such a teacher now?

I try, but not everything depends on me. There are male and female students who benefit from this and I can work with them effectively, while others just count on luck and wait for quick success. And all artists know that a work of art needs time – it has to take its time! Although I must admit that knowledge alone in the performing arts is not enough, but to achieve something you need to have a solid technical basis. To use a linguistic metaphor, the stage is dominated not only by grammar, fixed rules that determine the correctness of our syntax. There has to be a recipient of our message and what we give from ourselves. Then art can exist. I once stood on stage and repeated in my head what I always say to my students, watch this… watch that… until I thought, man, what are you doing, you can’t do it that way! Technique is extremely important, but more important is what you want to say to the audience.

Particular roles in your career that just required this triad?

Faust, Nabucco, the Black Mask, Tosca… I was persuaded to do Tosca by my wife, Aleksandra Lemiszka, a long-time soloist of Wrocław Opera.

Have you ever sung together?

Of course we have!

I suspect this may be more difficult than a duet with a neutral person….

This is the hardest thing! It’s only a semblance that in a duet with your wife you can afford to do more, on the contrary! Take the rape scene. Played with a close person, it requires an exceptional separation of private and professional worlds, and you have to be careful not to step on the train of the dress, because you can get later hurt at home (laughs). But well, theatre is a place based on relations, community, we have to be able to live together, because a team is what creates an institution – it can be liquidated with one signature, but it takes years to build it. We all work as unity: singers, orchestra musicians, technicians, tailors. You have to be aware that we are a place built on mutual relations.

To maintain good relations in such a large community certainly requires patience and above all humility…

Holy words, art requires great humility.

Are you humble?

I think it is for others to judge.

That is a very humble answer! After so many years in opera, what have you learned here?

I can go out and sing Baron Scarpia the way I sing and say enough to myself. I also learned the audience, how they can react, what energy and attention they can give to the artist. I remember the moment when I stood on the stage and I felt that this silence, this opposite tension that the people in the audience were directing towards me – that it was all mine at that moment.

I also learned that a soloist’s job is not just singing. It’s acting, movement and other additional skills that add up to the final result. In the vocal-acting department, we did drama for three years, and opera for three years. We learned such nuances as how to hold handmade paper and how to write with a goose feather. Everything requires different acting on stage! You have to know how to fall on the floor, how to dance. What was ballet for? I learnt it for several years, knowing that I would not become a dancer, but I had more confidence that if I turned around a few times on stage, I would not fall over.

These are strong foundations for what ultimately became your destiny, which is singing…

This also required time and the aforementioned humility – I knew when it was my turn and when I still had to wait. I received my first offer, the role of Zachariah in Nabucco, right after my studies at the opera in Bytom, and an offer of a three-room flat. I turned it down. I knew it was too early for me. It was not until 10 years later that I sang Nabucco at the Teatr Wielki in Warsaw. Then I sang these parts many times in different theatres.

My singing professor told me to remember about calmness, technique and then about interpretation. What’s more, she said I wasn’t ready for competitions! But I entered them anyway, because I wanted to test myself, to be judged by other people, to see how far I still lacked to become an artist.

Do you get emotional during performances? Emotions are one of the components of a good performance, but on the other hand, they can also ruin it…

I don’t allow myself to do that. I remember singing at my own son’s first communion, the tightness in my throat – never again! I know a situation when one of the singers just before the performance received the news that her daughter had an accident and was in a serious condition. The artist was speechless for six months, her emotions were out of control.

Is there a life outside opera? You will soon have a little more time to rest, to slow down…

Above all, I plan normality, I do not plan too much according to the old Polish saying: Man plans, God records. I am a fulfilled man. I have a family, a house, grandchildren and the time to free myself from this eternal rush, the constant complications in life. Everyone has some problems – in old age you want stability, peace and, above all, health. I look sometimes at my phone and see how many numbers will never call me again, but I’m not going anywhere! Unless it’s to a comfy chair to spend time with my grandchildren. There is truth, joy and openness to others in children. Attention and knowledge about the world should be passed on to them from an early age, even when their eyes are still a little blurry, when they are just learning to look at the world. This is the only way to bring up the next generation. By passing on the truth and teaching them tolerance and respect for others. And we will only teach them this when they see these values in us.

Interviewed by Katarzyna Aszkiełowicz

translation Karolina Mrozowska